This month I announce a shift in service at Peppler Occupational Therapy to offer more choices to parents and caregivers. Meeting a family where they are means providing services in a variety of ways. By ushering families through the 3 phases of progress and offering a variety of pathways to achieve progress more families can engage in important neuro-developmental growth. The life of a child and family shouldn’t be difficult and hard, together we can change that trajectory to a life that is easy and fun.

Vestibular System - The Foundation of All Movement

Sleep: The Foundation of Health and Well-Being

Message from Misti

Sleep plays a crucial role in our overall health, but many of us struggle to get enough of it. Whether you’re a child, teen, or adult, sleep deprivation can have serious consequences. Let’s explore the importance of sleep, how much we really need, and ways to improve our sleep habits.

Lack of sleep affects us all, but the consequences can be particularly harmful for children and teens. Signs of insufficient sleep include:

· Irritability and mood swings

· Learning and memory problems

· Increased susceptibility to illness

For adults, chronic sleep deprivation is linked to serious health conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and depression. Let’s explore what we need for a good night’s sleep and tools to help improve our sleep including the new Rest and Restore Listening Protocol.

REFLEX HIGHLIGHT: Abdominal Sleep Posture Reflex

The Abdominal Sleep Posture Reflex is a natural position where the body lies on the stomach, with the face turned toward a bent arm and that leg on the same side flexes up, while the opposite leg remain straight, and the opposite arm may extend up or down. Soft massage and muscle stretching is then provided to 5 specific neuro-tactile locations on the body. The position itself is calming to the nervous system as it turns off the auditory channels, allowing the brain to calm and move out of a state of vigilance. It brings about slower theta brain waves which are most common during the first phase of sleep.

Even if you are not one to sleep on your stomach and there is no one there to provide massage on the neuro-tactile points, placing yourself in this position can help you calm and get to sleep. You might realize this posture is the reverse of the Asymmetric Tonic Neck Reflex. Interestingly, engaging in ATNR repatterning exercises brings about the faster alpha brain waves which is the opposite effect we want before bed; thus, we do not recommend ATNR activities right before bed.

SENSORY CONNECTIONS: The Science of Sleep and the Nervous System

Our bodies follow natural sleep cycles controlled by circadian rhythms and the Vagus nerve system. The Vagus nerve helps regulate relaxation and recovery during sleep, while exposure to bright light during the day supports a healthy circadian rhythm.

The Autonomic Nervous System and the Vagus Nerve

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a crucial role in sleep regulation, balancing between the sympathetic (fight or flight) and parasympathetic (rest and digest) systems. The Vagus nerve, a key part of the parasympathetic system, promotes relaxation, slows the heart rate, and enhances digestion—creating the ideal state for deep, restorative sleep. Activating the Vagus nerve through deep breathing, meditation, and relaxation techniques can help improve sleep quality and overall well-being.

Circadian Rhythms, Sunlight, and Melatonin

Circadian rhythms are the body’s internal clock, regulating sleep and wake cycles. Light exposure plays a crucial role in maintaining these rhythms. Getting natural sunlight in the morning helps signal the brain to be awake and alert, while dim lighting in the evening supports melatonin production, the hormone responsible for sleep. Blue light from screens suppresses melatonin, making it harder to fall asleep. To optimize sleep, aim for at least 30 minutes of sunlight exposure in the morning and reduce screen time before bed.

How Much Sleep Do We Need?

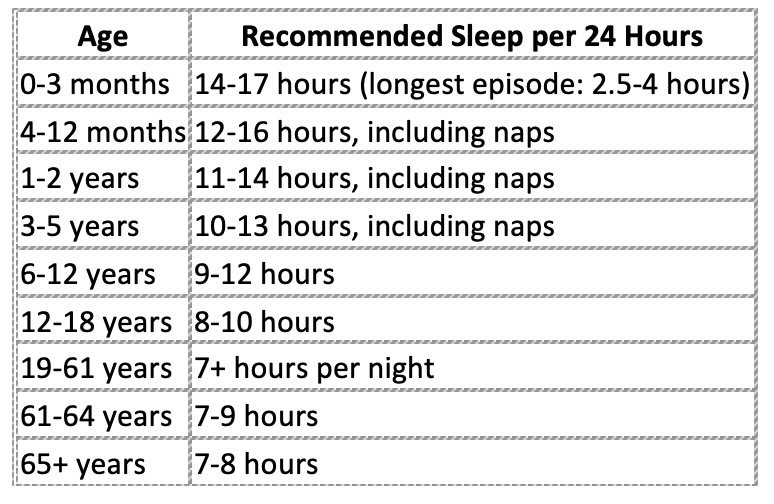

While individual needs vary, here are the general sleep recommendations from the CDC:

Sleep Challenges in Childhood Neurologic Disorders

Children with neurological conditions such as autism and ADHD often experience unique sleep challenges. Common issues include:

Difficulty falling asleep: Hyperactivity, sensory sensitivities, and anxiety can make it hard to settle at bedtime.

Frequent night waking’s: Children with autism and ADHD may experience more nighttime awakenings due to difficulties with self-soothing or increased sensitivity to environmental stimuli.

Irregular sleep patterns: Disruptions in melatonin production can lead to difficulty maintaining a regular sleep schedule.

Daytime fatigue and behavioral issues: Poor sleep can exacerbate attention problems, emotional regulation difficulties, and impulsivity.

To support better sleep in children with autism and ADHD, consider structured bedtime routines, calming sensory tools like weighted blankets, and behavioral sleep interventions.

For more details on children’s sleep habits, visit: Raising Children’s Sleep Guide.

Teen Sleep Challenges

Teenagers experience a shift in their circadian rhythms, leading them to fall asleep later (often after 11 PM) and wake later. Unfortunately, over 90% of teens don’t get enough sleep on school nights, which impacts concentration, learning, and mental health. This sleep deprivation is associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety in adolescents.

Sleep and Adulthood

As adults, our sleep is often disrupted by caffeine, alcohol, stress, and anxiety. Poor sleep hygiene further exacerbates these issues, creating a cycle of fatigue, poor mood, and decreased overall health.

Breaking Down Sleep Cycles

Each night, we cycle through different sleep stages, including:

Light Sleep (50-60% of total sleep time): This stage helps transition into deeper stages and is most common in the first half of the night.

Deep Sleep (15-25% of total sleep time): Crucial for physical restoration, deep sleep is most abundant in the first half of the night and decreases as the night progresses.

REM Sleep (20-25% of total sleep time): This stage, where dreaming and cognitive processing occur, increases in duration as the night progresses, with the longest REM periods happening toward morning.

To feel truly rested, we need to balance time in each stage and ensure we complete multiple sleep cycles throughout the night.

SKILL DEVELOPMENT: Healthy Sleep Habits

Good sleep hygiene is essential for quality rest. Here’s how you can improve your sleep:

Create a bedtime routine to signal your body it’s time to wind down.

Take a warm bath to promote relaxation. The effects of warming the body begin to wear off after about 20 minutes, so be sure to get into bed shortly after the bath.

Limit screen time before bed to avoid blue light exposure; recommended to limit exposure for 2 hours before bed.

Try weighted blankets or Lycra sheets for a calming effect on the proprioceptive sensory system.

Ensure adequate sunlight exposure during the day to support circadian rhythms.

Dim the lights in the evening to support melatonin production and prepare your body for sleep.

Engage in Vagus nerve-stimulating activities such as deep breathing, humming, or gentle yoga to promote relaxation before bed. See below about the new Rest and Restore music program to promote deep calm through Vagus nerve stimulation.

Exercise regularly but avoid intense workouts close to bedtime.

Avoid caffeine and heavy meals in the evening, as they can interfere with your ability to fall asleep.

Maintain a consistent sleep schedule, even on weekends, to regulate your internal clock.

Keep your sleep environment comfortable, ensuring your bedroom is cool, quiet, and dark.

By making small adjustments to our daily habits, we can improve sleep quality, enhance overall well-being, and set the stage for better health at any age.

New! Rest and Restore Music Program to Calm the Vagus Nerve

Listening to music modified for optimal rest and recovery of the nervous system can improve sleep qualitiy

Vagus nerve researcher Stephan Porges has paired with Anthony Gorry, a music and audio innovator to create a new listening program called Rest and Restore. This is a new tool to gently move into biobehavioral states of calmness and relaxation. Early research shows RRP may improve sleep, digestion, anxiety, trauma-recovery, and more. Misti is now a certified provider for this tool as well as reflex repatterning, if you are interested in using these tools to improve your ability to calm, contact Misti now.

Sweet dreams!

Childhood Trauma, Reflexes, and Sensory Strategies

The purpose of each reflex is to support our survival through birth and in the first few months of life. They protect us and help our nervous system build strong pathways we can then use for later emotional and motor control. The genetic code for each primitive reflex is then stored within the nervous system, ready to jump in to protect again when all other systems start to fail.

E-learning In the Time of Sheltering In Place

Stress levels are high all around, and supporting your child during this time of e-learning can be difficult, especially when they have learning difficulties and attention problems. Here are some tips taken from an ADDitude Webinar entitled Coronavirus Crash Course for Students with ADHD given by Ann Dolin of Educational Connections Tutoring, Test Prep and Executive Function Coaching and author of Getting Past Procrastination: How to Get Your Kids Organized, Focused, and Motivated . . . Without Being the Bad Guy and several other books about working on executive functioning.

Create a Routine (And Put It In Writing)

Kids crave routines, especially our kids with ADHD. If they don’t know what to expect, life feels loosey goosey. A routine allows life to go on autopilot. Remember to include the important daily routines: Wake-up, get dressed, mealtimes, and bedtime.

Some children may not respond to a strict schedule made in 20-30 minute increments of a specific subject or task. They may need more flexible timing such as work periods where they choose what to work on in the allotted time frame or station. Allow for that sense of choice, and use a timer to set the work periods.

When: Decide when your learning periods will be

Human energy and motivation has peaks and valleys through the day. Doing the harder tasks should be done in the morning. Around lunchtime is when we have our optimal energy. That’s why it’s important to do the harder tasks in the morning. In the afternoon we all experience a great dip in our energy level, which will come back up around 3:00, but not rise to our earlier optimal levels.

Pomodoro Style, a researcher from Italy found that when people have a specific amount a time they are more likely to get their work done. He also researched the optimal amount of time and found 25 minutes is best. After the breakfast routine is done, have a set start time and a large chunk of study time that is broken into smaller increments.

Where: Designate places for Learning

For younger children set up different stations for them to move through. Consider a library/reading station; a math station; a puzzle or lego station; a science station; and art area, a section of the table for writing. It’s not your job to keep them occupied at the station, it is their job to stay busy in the station.

Older students should have 2-3 spaces they can move between to complete work - but NOT their bedroom. Keep their learning places in the public areas of your home.

What: Organize what they will do each day

If your school is providing work to do, go through the assignments each day and make a list with your student (a whiteboard is great, but you can also just use a piece of paper). Divide it into 2 columns. List the things that need to be done this week on the right side. Next, list the things that need to be done today on the left side. Last, have your student break down the longer assignments into smaller tasks and have them list a small amount on the daily side. Be sure to cross off the assignments as they are finished, crossing things off a list gives a feeling of accomplishment.

If your school hasn’t provided work, here are some good websites that allow kids to engage in learning. It’s important to say “This is a priority, we are still going to engage in learning during this time. You can choose some areas of interest to study.”

You can find a lot of free resources to boost up your stations:

Scholastic learn at home

IXL.com - has very specific learning

Brainpop.com or Brainpopjr.com- it has a built in quiz that lets them know what they know and what they don’t know, and provides them some feedback.

Ask kids to figure out what they might like to do, have them select things they would like to practice or be more engaged in learning.

Breaks: We all need them, how to organize them

Optimal concentration time for an adult is 25 minutes, a little shorter for younger learners. Set learning sessions or stations up in set time frames. The same researcher who found that 25 minutes is the optimal work zone, also researched break times. He found a 5 minute break between sessions to be optimal, it is easier to get back to work after a short break. However, after several of these 25 minute work sessions, 5 minute breaks you will need a longer break. Older students should be able to do 2-3 sessions before taking a longer 20-30 minute break. Younger students may need a longer break after 2 sessions. It is important to have them figure out what the break is before the break - what will they do, make sure they know the time frame.

Other important points:

How do I convey to resistant learners this is not spring break/winter break, especially teens?

Ask questions to help them have more agency in the process.

What is something small you can do to keep up with your learning and work?

How much time can you commit to?

What can you get done in the next __minutes?

Asking a question helps them to be more open to ideas if they are part of it.

When you are working at home - Don’t expect the kids to be like you

Get them going, set very specific expectations, then walk away. Set aside times to check in and let them know when that will be so they can expect help at that time.

Ask your child: If you’re super stuck and you don’t know what to do, what is an option?

Ways to help kids learn time management and learn to regulate their own behavior.

These extensions/apps help show the passing of time and do not allow them to move into other apps. These will block the websites they really want to resist for that period of time, it’s a visual reminder ‘I’m in study mode.’ Have them list the things which really distract them, they usually can identify the things that distract them the most (youtube is a big one).

Stay focused, chrome extension for older students

Self control, for mac

Forest - for iPhone

Rewards are fine. But if you offer screen time, you can’t offer it any other time of day. Then it’s not as valuable. If your work is completed by x time, then you can play fortnight for x amount of time.

You can have activity rewards - if you get your work done, we can bake tonight, or we can have a dance party.

What should we do on weekends

Free time (within reason, not 12 hours of video games) especially if you have a resistant child, no school work

What about kids that are refusing to get outside?

Go outside with them, make it non-negotiable. Set a time and take a 20 minute walk. Everyone needs to get outside and get some movement. Let them know you understand why they don’t want to, but that afterwards they can do a self-chosen activity.

Suggestions for when you have kids at different age levels:

Set up stations for the younger child that are more hands on, things they really like to do. It will help them sustain their attention far longer. Still set up expectations of work, for 30 minutes it will be quiet time for everyone. The younger child can move through school work and the desired stations giving the older child longer work sessions.

We can’t beat ourselves up as parents.

You have to try it for about 3 days to find out if it really doesn’t work, or your child is just really pushing back. After 3 days you can re-adjust, does it need more structure or need to be more fluid?

I highly recommend watching the webinar, it’s about an hour long. Link to the webinar Coronavirus Crash Course for parents with student who have ADHD

Archetype Movements - The Basic Building Blocks

I’ve been working with these foundational movements for a couple of years now. While reflexes are about automatically responding to information in our environment, Archetype Movements are the biomechanical patterns that allow our bodies to move and respond. These 7 key movement patterns are found in all of our sensorimotor reflex responses, our automatic motor responses and our consciously controlled motor skills. They develop sequentially in utero; we are born with the innate ability to move through them. By using these patterns over an over, we build strong pathways in the brain that allow us to move with more complex movement patterns leading to skilled, conscious movement and choices.

So these patterns are important! If we haven’t built that strong brain pathway, we start to rely on less efficient motor schemes, we work harder and fatigue easier when we move. These patterns are so important, practicing them daily leads to brain growth that positively impacts learning and regulating our stress responses. The Masgutova Method recognizes 7 Archetype movement patterns and an 8th one that links all of the patterns together for purposeful movement.

1. Core-Limb Flexion Extension or 6 Ended Star: This pattern is about connecting our body center (gravity point) to our head, arms and legs. It allows us to be grounded and sets up the midline of our body. Emotionally it allows our Core Tendon Guard Reflex and Moro Reflex to function appropriately. Finding equilibrium between flexion and extension allows for postural control of the trunk to develop.

2. Horizontal Spine Rotation: Often associated with mouth-spine-rotation as the infant’s head turns toward a food source. As the infant matures other stimuli such as sights and sounds draw their attention and they learn to control the head and rotate toward information. This is foundational for rolling over. The eyes start to track, which is needed later for reading. Rotational movement is also known to improve memory.

3. Trunk Extension: Our genetic code demands that we go upright against gravity, trunk extension is about moving the head upright while stretching the feet downward. Toe walkers are often not able to do this; they are searching for upright without being grounded downward. Trunk extension allows us to organize around our midline, that invisible thread the runs through the middle of our body from our head to our feet. This movement relaxes the tension of the protective reactions of the cerebellum allowing for clarity when thinking. This pattern is the basis of reaching, taking and pushing and is good for awakening before test taking or new learning.

4. Lateral Flexion-Extension: In this pattern one side of our body is flexing to the side simultaneously while the other side is extending. It is the basis for locomotion or being able to stabilize one side of the body while the other is moving. It is needed for tuning over and plays a large role in our ability to move and respond to 12 different reflexes.

5. Homologous (Bilateral) Movement: Here we move both of our arms or both of our legs at the same time. The symmetrical movement is necessary for taking, pulling pushing, raising, etc. The purpose here is to form motor coordination between the right and left limbs such as clapping. By bringing either hands or feet together we gain an inner sense of our bodies midline.

6. Homolateral (Same Side) Movement: This involves the right arm/leg or left arm/leg moving in coordination with each other. The brain begins to access one hemisphere at a time, and dominance of one side starts to emerge. We are free to shift our weight from one side to the other across midline. Differentiated, specialized movements of the limbs develop. The affect of this pattern on learning leads to improved memory, improved motor planning and control, eye-hand coordination, and improved expressive language.

7. Cross-lateral Movement: This is about coordinating movement across body midline and from top to bottom (right arm/left leg or left arm/right leg). It is necessary for crawling, standing up, walking, running, and jumping. All skilled sports use cross lateral movements. It relies on all the other movement patterns to be fully developed. The brain begins to coordinate thinking between the detail oriented, analytic left side and the big picture, gestalt right side.

8. Intentional Movement: This last pattern coordinates all the other patterns together for purposeful, goal-oriented movements like reaching for an object. Intentional movements such as skipping, galloping or hopscotch develops. Movements transition into automatic skills. Precision and controlled movements for manual skills such as writing develop. Cognitively we can set goals, improve our timing and processing speed, as well as improved focus and selective perception.

When these patterns are not working properly, we can re-train the brain and body to bring automaticity, allowing freedom for the body to respond appropriately when reflexes are stimulated. The Masgutova Method has developed simple, repetitive movement exercises that allow the brain to form the strong pathways needed for automaticity and freedom.

One study demonstrated how incorporating these movements into a classroom daily helped to improve reading scores in kindergartners. A friend of mine was trying to complete such a study with a school district using a control group of students who didn’t get the movement intervention. With the introduction of Archetype movements reading scores in the test group improved rapidly. After four months the district suspended the study because they couldn’t justify not providing this movement based intervention to the control group.

These movements are powerful for allowing the brain to organize, which in turn allows for greater learning. Let me know if you want to learn more about them.

Moving toward Mental Health

It’s been quite a while since I sat and wrote here. Sometimes life throws a curve ball and you have to take time to sort it out. This past year has been a concentration on mental health – mine, my children, my partner. We are all working to manage our mental health crises and day-to-day functioning better. Coping strategies, toxic relationships, radical acceptance, family meetings, in-patient hospitalizations, black and white thinking, partial hospitalizations, day programs, substance use/abuse, these have all become common vernacular to me now. And I realize I am not alone – there is a growing multitude of parents who are learning these terms and living daily with children that are not able to cope and function in the society around us.

What better topic to write on as I venture back into the land of my professional life. Let’s look at some statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

· 13% of children 8-15 have a diagnosable mental disorder during the school years.

· One in ten youth have a disorder severe enough to impair how they function in the home and community.

· Just 50% of children with mental disorders received treatment in the last year.

· Half of all lifetime cases of mental disorders begin before age 14.

· 9.4% of children aged 2-17 (approximately 6.1 million) have received an ADHD diagnosis.

· 7.4% of children aged 3-17 years (approximately 4.5 million) have a diagnosed behavior problem

· 7.1% of children aged 3-17 years (approximately 4.4 million) have diagnosed anxiety.

· 3.2% of children aged 3-17 years (approximately 1.9 million) have diagnosed depression.

· Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youth 12-24 years old.

Depression and anxiety have increased over time

“Ever having been diagnosed with either anxiety or depression” among children aged 6–17 years increased from 5.4% in 2003 to 8% in 2007 and to 8.4% in 2011–2012.

“Ever having been diagnosed with anxiety” increased from 5.5% in 2007 to 6.4% in 2011–2012.

“Ever having been diagnosed with depression” did not change between 2007 (4.7%) and 2011-2012 (4.9%)

Reading these statistics doesn’t shock me, but I am greatly saddened. Add to this the crisis of opioid and drug use among teens and it’s no wonder that our schools are time bombs.

According to the CDC “Mental health in childhood means reaching developmental and emotional milestones, and learning healthy social skills and how to cope when there are problems” With that as the definition of what health is I’m left with so many questions. What are we doing wrong? What are we doing right? When there is a breakdown in any of this, what can we do to bridge the divide between mental illness and mental health? There are many smarter and more knowledgeable people than me studying this and I won’t pretend to be an expert.

I did do something professionally that changed my entire perspective on behaviors this past year. Beyond learning the statistics and vernacular, improving and utilizing coping strategies, better defining boundaries, refining my communication skills; I attended Svetlana Masgutova’s class on Stress Hormones and Trauma. The deeper understanding of our bodies stress response system completely changed my view on the meltdowns and breakdowns our kiddos are having. By intervening on the hormonal level we can reduce breakdowns and repair the ability to regulate. I’m hopeful that using reflex patterns and techniques aimed at releasing the protective stress response as well as increasing chemicals from the parasympathetic system like dopamine, serotonin and GABA can make substantial differences in the mental health of our youth. And not just our youth, we as parents need to support our own mental health and wellbeing. When an individual in a family system struggles with mental illness, stress increases for all family members.

If you or someone you know seems to being having difficulty navigating daily life, seek help. Talk to your family doctor about the symptoms you notice and they will help you navigate the next steps. Here are some organizations that can help you better understand what is happening and connect you with information and resources.

https://www.mentalhealth.gov/talk/parents-caregivers

https://www.nami.org/find-support/family-members-and-caregivers/learning-to-help-your-child-and-your-family

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/index.shtml

https://teenshealth.org/en/parents/emotions/

What’s the difference between School Based or Private Pediatric OT?

People are often confused about why a child would qualify in one setting but not the other, or why therapy looks so different in the two settings. Although occupational therapists are trained to help “people participate in the things they want and need to do through therapeutic use of everyday activities (occupations)” the goal or mission of the school or clinic setting is different, thus different models are used to deliver services. Private clinics use a Medical Model where the primary goal is to address medical conditions and to help a child realize their full potential. Schools use an Educational Model where the primary goal is to support engagement and participation in the curriculum and school setting.

In both settings a child must have a recognized disability or disorder that affects their performance. Both require initial evaluation to determine the need for service and continuous monitoring of the intervention plan once service is started. The intervention plan must document a student’s strengths as well as the limitations along with setting goals to help improve performance.

In the Medical Model, the interventions will address skills needed for tasks across a variety of settings: home, community and school. The overall goal is to help the child function to the best of their potential in all environments.

A doctor’s referral for services is required here in Illinois, while it is not always needed in the school setting.

A doctor can refer because of a specific disability or because of an apparent delay in development that needs to be addressed.

Children with mild, moderate and severe disabilities may benefit.

Therapy can address movement and regulation quality as well as function.

Therapy is usually delivered in a one to one setting.

Activities can address underlying deficits in order to improve higher skill ability.

Insurance may or may not pay for therapy services depending on the individual insurance policy.

Therapy often looks like play, as a therapist scaffolds difficulty in games and tasks to allow for development and progress toward the goals.

In the Educational Model, the interventions address skills needed in the school environment. The focus is on independence and functionality. The goal for services is that a child achieve within the average range of performance as same age peers or has functional alternatives rather than fulfill their best potential.

Direct Occupational Therapy services in the school are a related service, meaning the student must qualify for special education services due to academic concerns; a student can not qualify for direct OT services without an accompanying academic delay.

Schools often need to prove a percentage of delay from expected age norms, meaning the performance is below the average range, not necessarily just below the median or 50th %tile.

In other words, a child who does not perform to what may be his/her full potential but functions adequately, would not qualify for school based services.

An occupational therapist may consult with a team for a child who has a 504 plan, or a medical condition which does not affect academic performance but limits a students access to the building or curriculum. Consultation would include accommodations needed in the classroom, environmental changes that would allow for greater access, and strategies for staff to use.

Consultation with teachers and teams may also be provided during the Multi-tiered System of Support (MTSS) to help keep a student within the average range of functioning so that special education services are not needed.

Therapy is often delivered in a group, within the natural context of the classroom.

Therapy services are provided by the school district.

Goals are directly related to the functional activities/skills that are targeted for intervention, underlying foundational skills are not the focus of therapy sessions.

Often times children qualify and receive therapy in both settings. A child may have delays at school and need occupational therapy to enhance their participation in the approved curriculum, as well as have delays in daily functioning within the family and community. Often school therapists will work on handwriting and fine motor skills development, while the clinical therapist will work on social skills, regulation and many of the underlying foundational skills. In these situations it is best when the therapists from each setting can talk with each other, sharing insights about the child as well as what the goals are and how the child is progressing toward accomplishing those goals.

There are many reasons why a child would need clinical OT services even though they are receiving it at school. The foundational skills needed for holding a pencil to write are the same foundational skills needed to hold and use eating utensils or a paintbrush or sidewalk chalk. Visual scanning is necessary for reading as well as scanning a room to locate a specific toy or a second sock while getting dressed. A child may have attention/regulation issues in school that interfere with learning, while in the home parents need strategies to get through the morning routine and out the door in time for school. There also may be times a child has room for improvement in fine and visual motor skill development necessary for handwriting, cutting and reading; but not qualify for services in the school. In all of these instances, private clinic based services can help a child reach their fullest potential.

Having worked in both settings, I fully understand the limitations of the Educational Model – therapy in that setting is for a different purpose than providing private occupational therapy. Therapy in the school setting is not meant to be a replacement for clinical therapy. Students who need therapy in the school setting often have disorders that affect life outside the school as well, and private therapy is there in a more expansive manner to help a child navigate all aspects of life.

The Impact of Reflexes on Sensory Regulation

So many times children are referred to occupational therapy because they are having problems with self-regulation. Some people are OVER responsive to information – becoming easily overwhelmed leading to emotional meltdowns. Others are UNDER responsive, needing so much more information to just notice it – they seem bored, spaced out and aren’t available to take in new information. And yet others need so much more information that they will do anything to seek it out, and the seeking interferes with accessing what’s happening around them in that moment. The difficulty with self-regulation is it is one of those murky problems that has such a wide variety of symptoms and related behaviors; progress often feels like one step forward and two steps back. In all instances the person is not able to remain available for comfortable interaction with the materials, items and people in the environment around them.

Having studied and worked with kiddos that have “regulation difficulties” over the years I’ve used a variety of tools. Some of those are what we call top down strategies, they require cognitive problem solving to use different strategies to change their own state of regulation. The Alert Program and Zones of Regulation are examples of these top down strategies. Sensory Integration theory utilizes a bottom up or body based strategy that allows input through the body to influence the nervous system and change a person’s state of regulation. By filling up the body’s needs or changing the environment to reduce the impact of environmental sensations we allow the nervous system to regulate.

In recent years I’ve found that all of the above tools have some effect, but they aren’t treating the underlying cause of sensory regulation problems– they are treating the symptoms. The behaviors that we observe are symptoms of a nervous system which is not effectively dealing with perceived threats from the environment.

Individuals who have difficulty regulating their arousal level are often described as being in a fight or flight response. This is a physiological response to a perceived threat or harmful event. This response is triggered by the Moro Reflex. If our Moro Reflex does not become fully integrated, we easily move into that fight or flight response at what seems to be very slight threats. An individual might become very angry and have an over reaction, or they may engage in avoidant behaviors, trying to get away from the situation.

A similar response would be to freeze – to not engage, or respond. These individuals often look like they have low arousal; they aren’t paying attention to what’s going on around them. In reality, their nervous system is feeling threatened and going into a different physiological state brought on by the Fear Paralysis Reflex. This reflex protects us by having us stop, almost like a opossum playing dead, until the threat is gone. It should integrate by the 3rd year of life, and when it doesn’t our nervous system will rely on this inadequate response as a coping strategy.

More and more I find that the “on the go”, hyperactive individual keeps moving because they don’t have core stability – the Spinal Galant Reflex and/or the Spinal Perez Reflex aren’t integrated properly. These spinal reflexes are responsible for the development of our proprioceptive system, coordination of our legs and body core, postural control and attention. When they are interfering our body stays in motion to compensate for the lack of coordinated stability.

All of these reflexes are processed in the Brainstem or Diencepholon, meaning our brain processes all of the sensory information and forms a physiologic response before the information even reaches the Cerebral Cortex where we can “think” about the threat level of the information. By normalizing the responses of these reflexes, we are teaching the nervous system to respond to input in an ordinary way; allowing the nervous system to remain in a relaxed/ready state instead of a hyper alert state. This is the beauty of working with reflexes; we are effecting lasting change in the nervous system that translates into improved regulation. We are no longer just addressing the symptoms; we are getting at the cause of the problem.

What’s the value in an evaluation?

Many times parents ask if they really need a full evaluation. Evaluations are expensive and time consuming. They may have one from the school or their child had been in therapy before. They just want to get down to the therapy, to get to the fix.

Over the years I’ve come to value this important step in the therapeutic process more and more. In the schools we formally re-evaluate every three years and there are years I can’t wait for that re-eval year to come up again. Even though I work with a student weekly, the process of formal evaluation brings me so much information I can’t get in weekly sessions. I often go back and re-read evaluations after months of working with an individual. It keeps me centered on the presenting problems, allows me to see where growth is taking place and areas to focus on next. That’s why it’s important to do a thorough evaluation in the beginning.

So what makes an evaluation valuable?

Let’s look at the components of the evaluation. There are the formal assessments, the clinical observations of behavior and movement, the interpretation or analysis of all that information and finally the recommendations and treatment plan that comes out of it. Formal assessments are the standardized tests and rating scales which allow us to compare skill performance to same age typically functioning peers. Some of the assessments help to narrow down exactly what pieces aren’t working as well, and where a child’s strengths lay. Scores can be compared over time to demonstrate growth. The limitations of standardized tests are that they demonstrate what a child can do, but they do not indicate how a child does it. What does it take to get that result? How is the child moving, holding themselves, reacting behaviorally? That’s where clinical observations play an important role. Observations give the depth and background that help inform who the child is. Clinical observations are sometimes formal, specific activities/actions that are done to see how a child carries out the action. Other times they are the informal observations regarding how a child reacts. All of this observational information is important in describing the individual, what’s working and what’s not working. The standardized tests will give us numbers, the observations will give us context.

Both the formal assessments and the observations produce information. It’s then my turn to look at all the information and ask Why? Why is this individual not functioning at optimal? What pieces are holding this child or person back? What pieces can we use to build on to strengthen skills and perceptions? My education and training as an occupational therapist allows me to analyze the information in relation to the roles that person holds such as family member, student, team mate, worker, musician, community member etc. How is this person and their family affected by the deficits that were identified?

That leads right into the last and most important part of an evaluation – the recommendations and treatment plan. Now that we know all of this, what do we do about it? I always start with education – what does this family need to know that will make the therapy process successful? Do they need information about how the body processes information? Do they need to know how to adapt activities or the home to increases success and decrease stress? Will they understand the importance of the home activities and be able to implement them? Do they need a referral to other professionals that can also help? This is the starting place – the learning phase. Which is just as important as the actual therapy. When the education base is in place, the therapy has maximum benefit.

Finally there is the plan. What are we going to focus on right now and set as goals? Hopefully by this point the parents have shared their goals and desired outcomes, which are incorporated into the treatment plan. The goals are broken down into achievable and measurable objectives. Different methods are identified to achieve those goals. And most therapists agree that a key to making progress on those goals are the incorporation of a home program, which is outlined here as well. It’s the blueprint or working document for coming therapy.

Here is where a full evaluation becomes so valuable – once those objectives are met, we go back o the evaluation and decide have we met the goals or are there other goals to work on. A good evaluation will outline the next phase of treatment. A long the way we re-evaluate using the same tools to help measure progress. The value of the evaluation is that it provides the frame for progress to take place. Because in the end we all want progress for a better outcome.