When I was a new mom to my adopted newborn twins I had this idea of who I wanted to be as a mother. but the children who showed up in my life had nervous systems that required very different ways of interacting and being a mother. While these twins came straight from the hospital to our home, we didn’t have any idea what the prenatal life and birth had been like. Nor did we fully understand how the separation from the only heartbeat and voice they had ever known causes deep trauma. So many of us are parenting or teaching children yet we have no idea what traumas they have experienced. Sometimes we do know – Adverse Childhood Experiences is what they are now called. Poverty, loss of a parent, verbal abuse, physical abuse, neglect, substance use in the household, divorce. The kiddos we are raising and working with have life experiences which have caused nervous system reactions to protect themselves. What do we do with that?

Reflex Spotlight: Emotional Trauma and Reflexes

A reflex is a genetically programmed response to sensory stimuli. The purpose of each reflex is to support our survival through birth and in the first few months of life. They protect us and help our nervous system build strong pathways we can use for later emotional and motor control. The genetic code for each primitive reflex is then stored within the nervous system, ready to jump in to protect again when all other systems start to fail. When we experience high stress events outside the experience of our nervous system responses, these reflex codes resurface to protect us as we build new pathways to deal with this new stressor. However, if our circumstances do not allow us to find safety and resiliency, the nervous system may continue to use and rely on these genetically programmed responses which are, by nature, immature methods of coping. Repeated firing of these protective reflexes after a high stress event keeps the body’s resources focused on protection and survival. This is called negative protection. Here are some of the most active reflexes that may resurface during trauma. First, let’s examine the reflexes that can cause negative protection:

Tendon Guard – This is a general response of the nervous system related to muscle tone, causing muscles and ligaments of the body either to tense and bring the body into flexion to freeze, or allows over extension to move (fight or flight). Overall postural control is affected by this reflex reaction. Continued contraction of the tendons and muscles of flexion leads to over-activation in the brainstem, hindering thinking in the cortical areas affecting cause and effect thinking. When the stress or trauma is intense, the nervous system moves to recruit either the Fear Paralysis Reflex or the Moro reflex.

Fear Paralysis Reflex– This reflex is a whole body withdrawal and extension of the limbs, with one sharp intake of breath and then freezing in order to take in more information. It can be brought about by auditory, visual, or tactile/proprioceptive stimuli. A child who is stuck in Fear Paralysis will have shallow breathing; their eyes may constantly move to scan the environment for further danger and they may give less eye contact. This is the kiddo that goes into shut down, not able to form a response at all. When a child’s Fear Paralysis is constantly jumping in, they may appear hyper aware of all sensory input, and confused about making choices, not able to attend to what’s right in front of them. These kiddo’s often like to hide out in small spaces or under tables. Fear Paralysis reflex matures into the adult startle reflex and becomes lifelong.

Moro – This reflex has 3 stages of response: an intake of breath and expansion of the core while the limbs extend, then flexion of core and limbs with exhale, and finally moving into a an embracing posture. In homo sapiens development the infant prepared to squeeze and hold onto the caregiver as the duo moved to safety. The purpose is to prepare for fight or flight. The Moro reflex activates and responds within the sympathetic nervous system, before a cortical or emotional response can be noted. Children who are functioning with an overactive Moro and exhibit the flight response are the ones that elope from the activity, ask to go to the bathroom to avoid frustrating tasks, or wander around or pace when agitated. Those exhibiting the fight response often refuse or become argumentative, some may exhibit more forceful behaviors such as throwing items, hitting, kicking and biting when frustrated. When the Moro reflex is constantly triggered, the individual will exhibit poor focus with difficulty concentrating and may appear to be hyperactive. These kiddos may seem clingy or be very dependent on adults for guidance each step of the way.

Now let’s look at reflexes that work to restore protection by grounding and stabilizing our nervous system. These reflexes can strengthen our sense of felt safety, by telling us that we are on solid ground and able to protect ourselves.

Grounding Reflex: This reflex is lifelong, meaning it is intended to be used throughout the lifetime. It is the body’s ability to organize postural control against gravity, no matter what position we are in. It tells the body about the direction of the ground, helping us find steadiness in relation to the ground. When standing, we need to line up the center line of gravity through the trunk above the arch of the foot to place it in optimal position to stay connected to the surface. It helps us to feel stability and balance.

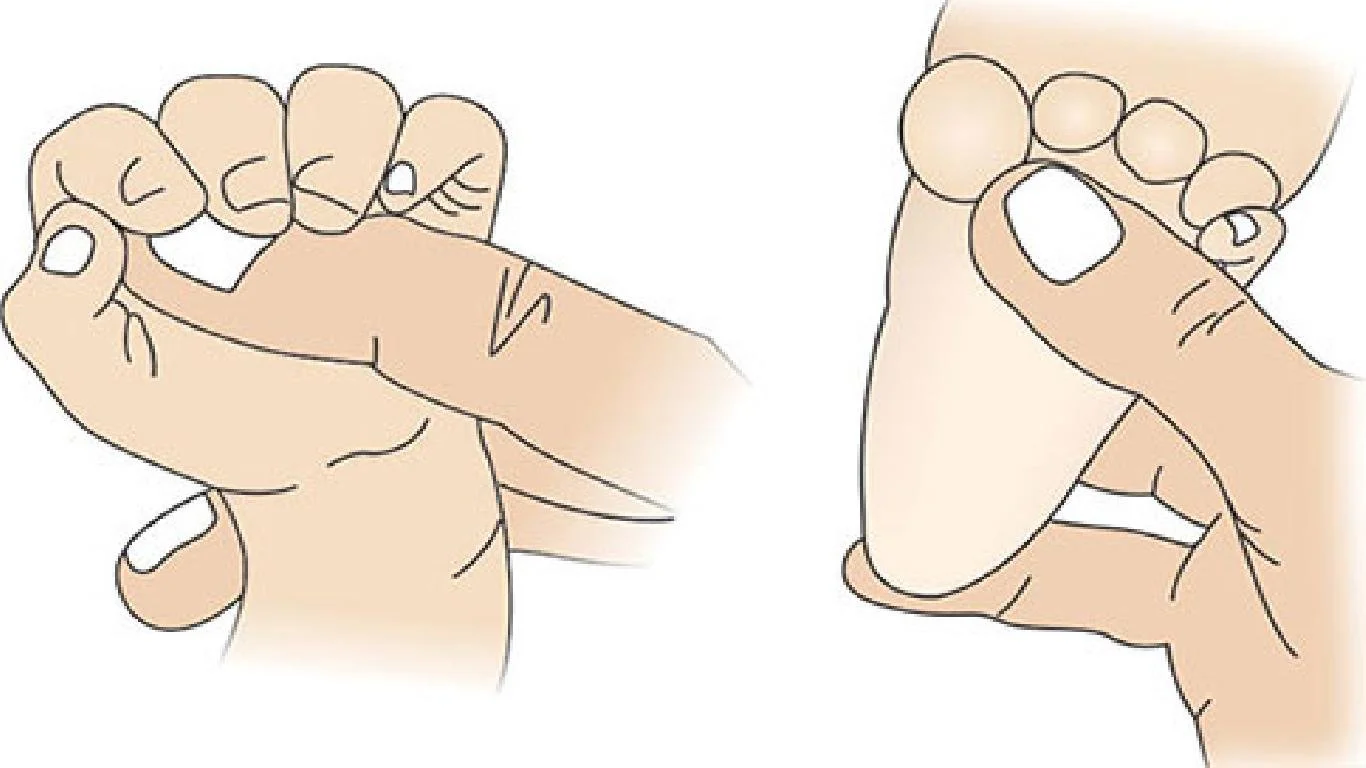

Hand Grasp Reflex: While the Robinson Hand Grasp Reflex is often associated with fine motor skills, there is also the emotional element of being able to “hold on for dear life” and “grasp” the larger picture of what is happening. The sensory stimulation for this reflex is along the top part of the palm, and the mature response is to be able to close all fingers with the thumb on the outside of the fist and hold tight. I’ve found that when a child struggles to understand safety, working on Hand Grasp helps them to find a sense of control.

Foot Grasp Reflex: Another lifelong reflex, when the center of gravity is shifted forward while standing the toes flex and grip into the surface to assist in maintaining balance. It is an important reflex for an individual to feel they can stay steady and not fall over.

Hands Supporting Reflex: This reflex is related to protective extension when the arms automatically come out to break a fall. The emphasis of this reflex is to be sure the hands are in optimal position of being open and facing outward as the arms extend to push back slightly as they encounter a surface, as well as observable shock absorption in the elbow. This push back and shock absorption protects the bones of the arm from breaking as the force of the body bears down on them. The emotional meaning of this reflex is about setting boundaries, keeping danger at arm’s length while having the flexibility to allow those who provide safety within reach.

While there are other reflexes that are important for healing after trauma, these are the first ones I check and strengthen when dealing with emotional stress. As noted earlier, these reflex patterns support our survival and development, they are genetic and already available within our nervous system. We can use integration techniques to decrease their negative protection and strengthen our sense of well-being. If you are interested in experiencing relief from emotional stress and trauma or know a child that could benefit, contact me for more information on how this is achieved.

Sensory Relationship:

Deep Pressure Touch and Calming

Touch plays an influential role in human development and emotional regulation. Touch communicates emotion in an intense way. Research has shown that soothing, safe touch reduces cortisol (the primary stress neurotransmitter) while increasing dopamine (which has a role in controlling memory, sleep, mood, concentration and feelings of pleasure), serotonin (which also affects mood, sleep, and digestion), and oxytocin (which acts in anti-stress like ways in reducing blood pressure and cortisol levels). Certain types of touch can be used to assist the nervous system to regulate by reducing the effects of the autonomic reactions like fight, flight or freeze.

There are 12 different types of tactile sensory receptors, some made to excite and alert us to problems (pain, temperature, light touch) while others help the nervous system to calm down and bring about a sense of relaxation or positive feelings. The goal of using touch with a child who has experienced trauma is to create safety and reduce on-going stress. Of course, we would never force a child to engage in tactile input, but would provide opportunities to experience these calming forms of sensory input to help them maintain regulation. The activities might be presented as choices in a sensory diet or be made available after a child has not been able to maintain regulation and has had a meltdown. Remember, using touch helps to reduce the cortisone racing through a stressed nervous system.

ALERTING TOUCH:

Light touch

Unexpected

Dabbing or poky in nature

In the area of the face

Approaching or on the head

Moves hair

Source is rough in texture

Source is cold to the touch

Source has intricate shape

Source has sharp corners

Source is sharp

Cold or cool environment

CALMING TOUCH

Pressure touch

Tight wrap

Firm stroking over large area

Familiar & predictable

Soothing or comforting

Source is smooth to the touch

Source is warm to the touch

Source has simple shape

Source is rounded

Source is dull or blunt

Warm or hot environment

In understanding the types of touch that can be calming, we are able to provide different touch opportunities in different settings. While in the home a caregiver can provide firm, long pressure touch through the arms and legs, that may not be possible in a school setting. In the school setting you could use:

a weighted blanket or weighted stuffed animal.

rolling up in a blanket like a burrito

being “squished” between large pillows or bean bags.

A way to incorporate soft, rounded input over large areas of skin is to use dried beans in a large tub, I often keep one that kids can climb into and bury their arms, legs, hands or feet in.

I’ve also used Dot’s and Squeezes with kiddos in a school setting, having the child imitate me as I slowly provide pressure into the palm of my hand, then squeeze my other arm slowly as I move up the arm.

In the home more direct contact can be made:

using lotion with long, slow strokes.

A warm bath and wrapping up in a soft towel afterward.

A great big, bear hug!

Dr. Masgutova believes so firmly in the healing power of touch she has created an entire protocol with 24 different neuro-tactile techniques. This protocol and the techniques are a cornerstone of the work done at any family conference and with all individuals who have experienced physical or emotional trauma.

Skill Development: Heavy Work and Proprioception

Often children who have experienced emotional distress have nervous systems that are continually running on fight or flight, even when the “threat” is small or doesn’t appear to us to be a real threat. The flight or fight response worked for them in their time of great need and they rely on it now, which blocks access to using more appropriate coping skills.

Let’s look at what happens in the body during a fight or flight response. The pupils dilate in order to take in more light and see better. The heart races and blood pressure increases as it prepares to provide greater blood flow while breathing becomes rapid to provide more oxygen during the physical exertion of running or engaging in battle. Adrenaline and cortisol begin coursing through the body to give energy to muscles, and one might feel twitchy or start trembling. The body needs to move; asking someone whose fight or flight response has been triggered to calm down, sit down with a weighted blanket, or allow deep pressure activities to happen is counter-intuitive to their nervous system. After the response is triggered, it can take 20-30 minutes for a typical nervous system to return to a calm state. If the individual’s nervous system isn’t typical, or they are not able to access more mature coping strategies, that calm down time can be greatly extended. You may know a kiddo like that – meltdowns last for 40-60 minutes and, once calm, they can be easily set off again.

So, let’s give that body movement in an organized way, a way that helps the nervous system allow that adrenaline and cortisol to be expelled and increase the serotonin and dopamine. Only then can a child process information and emotions. One of the greatest organizing forms of physical activity we can offer is heavy work. Heavy work refers to the engagement of proprioceptors–receptors located in joints, muscles, tendons and deep within the layer of skin. These receptors tell our brain where our body is in space. Heavy work activities create resistance input to the muscles, and involve pushing, pulling, squeezing, lifting, carrying, climbing, and chewing. Think of how your body feels after lifting weights or doing yoga; there is a sense of calm. We can help our kiddos achieve that.

In the home heavy work activities abound. We can often see when our child is moving from regulation into a flight/fight response. Keep several of these options available to offer when you see your child is on edge or beginning to meltdown. Presenting them in a “menu” or visual chart format will reduce the higher-level language processing needed to recognize and choose during stressful times.

Your child may not see the point or understand the purpose of the activity, so try to make them functional with “Can you take this/do this for me?” And remember, these aren’t punishments or rewards for behavior that has already occurred, they are alternative ways for the child’s nervous system to regain regulation before talking through the incident.

In schools it is more difficult to stop and help a student engage in heavy work in the moment a meltdown starts. While whole class movement breaks are common, they don’t always incorporate the heavy work needed or can’t be taken when a student needs it most. I like to incorporate a Heavy Work Station in classrooms. A place to the side where a student can be encouraged to go which is set up with heavy work choices. The activities utilize the child’s body weight and sometimes resistance bands to increase work load on the muscles. After they have chosen 1-2 work choices, they should finish with a touch or grounding activity to gain maximum benefit. The choices for younger students are different than for older students. By placing the choices on with Velcro dots, a student can create a different experience each time they visit the station.

An example of a chart to create a heavy work center for a classroom

When a large meltdown or disruption occurs in a classroom, there are likely other students who are experiencing stress just by observing it. The whole group might benefit a heavy work break. I’ve helped classroom teachers create whole classroom Heavy Work Breaks which incorporate greater amounts of heavy work and not just a movement like dancing. Small activity cards glued on popsicle sticks can be held in 3 cups: movement (vestibular), heavy work, and centering. One stick is selected from each cup and completed in the above stated order, this allows the nervous system to expend that intense need to move and quickly return to a state of equilibrium. You can find some premade cards here on etsy and I really like this curriculum from Print Path OT on teachers pay teachers.

The great thing about heavy work is that it has a mediating effect on the nervous system whether a child is in fight or flight and needs to move, or is in freeze and needs to move. Getting the body moving in an organized way along with incorporating breath work is regulating for the nervous system no matter how the child arrived at the need. These activities are great to teach as coping strategies. A child can choose and engage in an activity as they start to feel panic, stress or anxiety; before a full meltdown occurs. As such, the child is learning to short circuit the nervous system response cycle and move to regulation sooner.